“China is the invisible elephant in the room,” said Ying Chan, moderator of Covering China: Tips and Practices and founding director of Hong Kong University’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre. “Investigative Journalism for China is also important. It can be done. It’s being done. It’s very challenging.”

Two Chinese journalists and a London-based editor shared their experiences on how they have managed the challenging task of investigating China.

One Chinese journalist spoke on investigating one of the deadliest chemical explosions in China’s history, this August in Tianjin, a municipal city next to Beijing, killing 165 people, injuring about 800 and destroying 17 thousand homes.

The closest residential buildings were only 600 meters away from the explosion which took place in an illegally set-up warehouse, leading to the evacuation of about 30,000 residents.

Due to a lack of transparency the cause of the explosion remains a mystery.

However, by obtaining the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) from an environmental expert, and comparing it to a list of stored chemicals at the explosion spot, the reporter found that the company stored chemicals illegally, including excessive amounts of sodium cyanide—70 times the permitted amount.

In China, public records in the environmental sector are easier to obtain than those in other fields, the reporter said, adding that interviewing academics, who are more likely to talk freely than those from government research institutions, is a key part of the research process.

In addition to environmental records, there is public data available of the business registry and online stocks. Although disclosure is limited, it can give reporters leads.

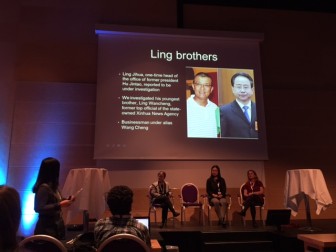

Wei Zhou, producer at BBC China, talked about how she investigated the unusual investment made by the brother of a disgraced top official in China using such public databases. Ling Wancheng is the younger brother of Ling Jihua, top aide to former Chinese President Hu Jintao, who fled to the U.S., according to the New York Times.

During the investigation, Zhou found that Ling Wancheng invested in seven companies and cashed out a large amount of money: US$62 million after IPOs. So, she used the registry of government-run companies, which provide basic company information including shareholders, directors, investment, detailed company registration documents which include such information as ID numbers, home addresses, and shareholders. She also used the stock transaction records to identify the top 10 investors.

The documents helped Chinese journalists push forward their investigations.

Christine Spolar, the Financial Time’s investigative projects editor, led a team of journalists digging into the trading of a little-known Chinese solar equipment supplier that became a company worth US$40 billon. Spolar’s team first reviewed the company’s documents and then dug deeper by looking at financial statements and bank notes. The team downloaded a huge data set of the company’s trades over the course of two years and conducted a detailed analysis.

Christine Spolar, the Financial Time’s investigative projects editor, led a team of journalists digging into the trading of a little-known Chinese solar equipment supplier that became a company worth US$40 billon. Spolar’s team first reviewed the company’s documents and then dug deeper by looking at financial statements and bank notes. The team downloaded a huge data set of the company’s trades over the course of two years and conducted a detailed analysis.

Christine added that it is always good for editors to read the journalists’ notes to find hidden clues.